Title : Censys: A Map of Internet Hosts and Services

Authors : Zakir Durumeric, Hudson Clark, Jeff Cody, Elliot Cubit, Matt Ellison, Liz Izhikevich, Ariana Mirian (Censys, Inc. Ann Arbor, MI, USA)

Scribe : Xuanhao Liu (Xiamen University)

Introduction

The problem of how to continuously maintain a comprehensive, accurate, and up-to-date global map of Internet hosts and services is important and interesting because enterprises, governments, and researchers rely on this internet scan data to remediate security vulnerabilities, track supply chain dependencies, uncover attacker-controlled infrastructure, and study internet behavior. However, existing systems and tools have significant shortcomings. While high-speed scanning tools like ZMap and Masscan have reduced the time needed to conduct an internet-wide scan, a single scan only provides a snapshot of a specific protocol and port at a single point in time, failing to address the challenge of continuously tracking billions of constantly changing internet services. Early internet search engines (including the original 2015 version of Censys and Shodan) commonly suffered from problems such as insufficient coverage and poor accuracy due to stale data. Furthermore, the complexity of real-world internet services—such as services deployed on non-standard ports, the short lifespans of cloud services, and the “fractured visibility” caused by geoblocking and network partitioning—makes building and maintaining an accurate map of the internet exceptionally challenging.

Key idea and contribution :

The Censys system has evolved from being a purely academic provider of scan data into a comprehensive, user-friendly map that maintains internet entities (such as hosts, websites, and certificates). Its core philosophy shifted from “how to collect scan data” to “how to build an entity model that is intuitive for users and accurately reflects the current state of the internet.”

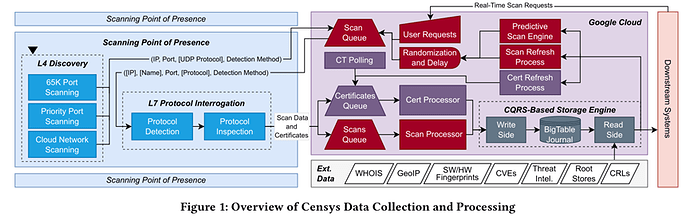

To achieve this goal, the authors re-architected every component of Censys. In the data collection stage, Censys employs a continuous “two-phase scanning” method.

The first phase is Service Discovery, which combines comprehensive scans of all 65,000 ports across the IPv4 address space, prioritized scans of high-churn areas like cloud networks, and a crucial predictive scanning engine that uses machine learning models to predict likely service locations, efficiently discovering services hidden on non-standard ports. Simultaneously, Censys scans from multiple Points of Presence (PoPs) in various geographic locations such as North America, Europe, and Asia to overcome visibility issues caused by network partitioning.

The second phase is Service Interrogation, where Censys performs application-layer (L7) protocol identification and deep handshakes with discovered potential services to obtain structured, non-ephemeral data.

The paper’s greatest contribution is that it systematically reveals for the first time the internal architecture, design philosophy, and evolutionary journey of a top-tier commercial internet search engine, providing the community with invaluable transparency. The authors detail how they process data: using an architecture based on the Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) pattern, they efficiently handle the massive volume of scan data writes and user query reads. The data pipeline not only stores raw information but also derives high-level context such as device manufacturer, software version, and vulnerability information, ultimately integrating it into user-friendly entity records like ‘Hosts,’ ‘Web Properties,’ and ‘Certificates.’ Furthermore, Censys prioritizes data accuracy over coverage, actively pruning service records that have been unresponsive for more than 72 hours to ensure the data users receive is current and valid. This series of designs and practices provides an important reference and example for how to build and maintain a large-scale, high-fidelity internet mapping system.

Evaluation

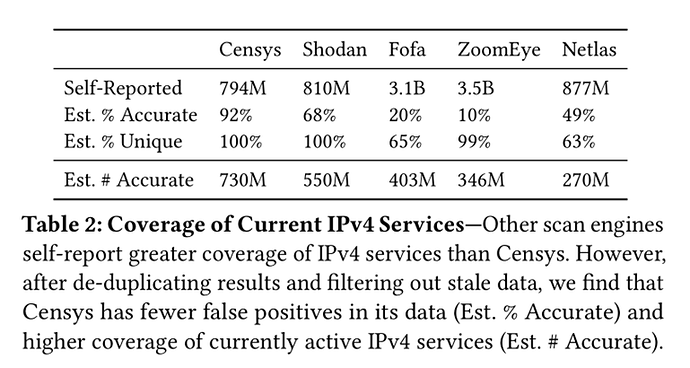

In the evaluation section, the authors compared Censys against four other major scanning engines (Shodan, Fofa, ZoomEye, and Netlas) as well as an “approximated ground truth” dataset built by randomly sampling scans across all 65,000 internet ports. The evaluation focused on two main dimensions: coverage (how many services an engine can discover) and accuracy (whether a service reported by the engine is actually online at query time). The results showed that while other engines might self-report a higher number of services, Censys leads in both data accuracy and coverage of currently active services. Censys’s data accuracy reached 92%, whereas other engines ranged from only 10% to 68%. After filtering out stale and duplicate data, Censys was found to discover 33% more active services than the next leading platform. This advantage is primarily due to Censys’s aggressive strategy for pruning stale data and its broader coverage across all 65,000 ports, enabled by its predictive scanning engine. Furthermore, in an experiment testing the speed of service discovery, Censys found newly online services in an average of 12.3 hours (median 5.7 hours), which was significantly faster than Shodan’s 76.5 hours (median 60.9 hours).

This result is significant because it reveals that in security operations and network research, data quality is far more important than raw quantity. For practitioners who rely on this data to respond to vulnerabilities, track threats, or assess network security, a “larger” dataset filled with stale and invalid information not only wastes valuable time but can also lead to flawed decision-making. The evaluation of Censys demonstrates that a system that prioritizes data freshness and accuracy can provide users with more reliable and actionable insights.

Q : You mentioned that 3% is not visible, which is the most interesting part. Do you have any ideas on how to investigate this 3%?

A : Yes, that’s precisely the crux of this difficult issue: How do you do it? Part of it can be found programmatically. Another part involves a great deal of fingerprinting, analyzing context, and making sense of what those things are and how they ended up there. To a large extent, it’s about understanding the “why.” What are these devices? Who deployed them? Is this a network-based pattern? Is it a manufacturer-based pattern? Or is it a pattern that resulted from those devices being compromised? But many of the questions ultimately boil down to whether you can figure out the pattern. If you can figure out the pattern, you can then predict where the other (invisible) parts will be. Some of them you simply won’t be able to find at all. Some things you can only find by brute-forcing the names, or discover through Passive DNS. But a large part of it depends on how much of it is predictable, and how you can build better prediction models for where those things will be and when they might appear.

Personal thoughts

The authors not only detail the internal architecture and design decisions of a successful commercial-grade system, but also candidly discuss the challenges encountered during operations, such as how to balance data coverage with accuracy, how to design user-friendly data models, and the ethical and human dilemmas faced when running an academic research program. This sharing is invaluable for the entire network measurement and security community, as it enables researchers to use Censys data more scientifically and provides a model for other projects hoping to translate research findings into practical applications. Given the growing importance of IPv6, an important open question worth exploring is how these mature scanning and data processing concepts can be extended to the IPv6 address space in the future. Overall, this paper serves not only as an excellent technical report but also as a valuable case study on how to successfully transition academic research into practice and ensure its continuous evolution.