Reflections on the research/product design process

Speaker: Vyas Sekar (Carnegie Mellon University)

Scribe: Jinghui Jiang, Yao Wang (Xiamen University)

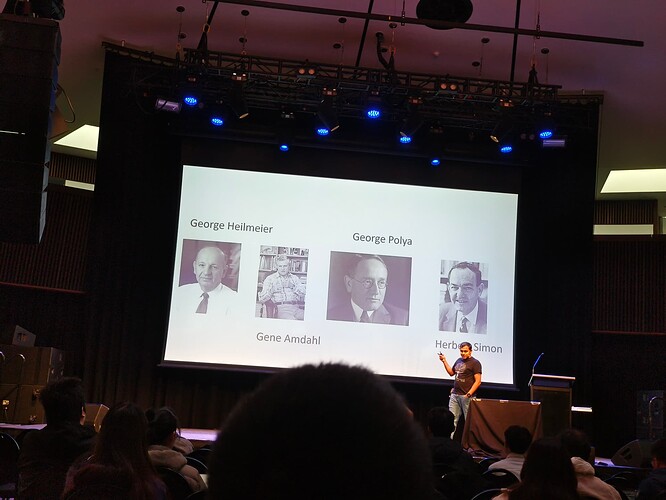

This talk focuses on the meta-process of research, drawing wisdom from four eminent figures: George Heilmeier, Gene Amdahl, George Polya, and Herbert Simon.

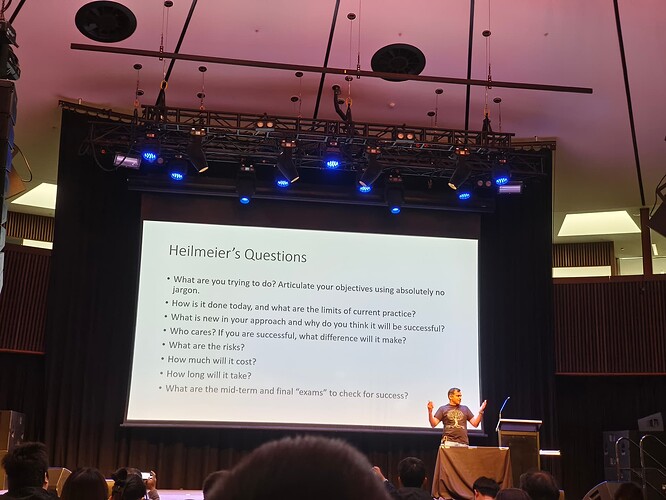

Heilmeier’s Catechism:

The speaker emphasizes the importance of clearly articulating research goals using Heilmeier’s questions:

The speaker stresses the need to revisit these questions throughout the research process as understanding evolves.

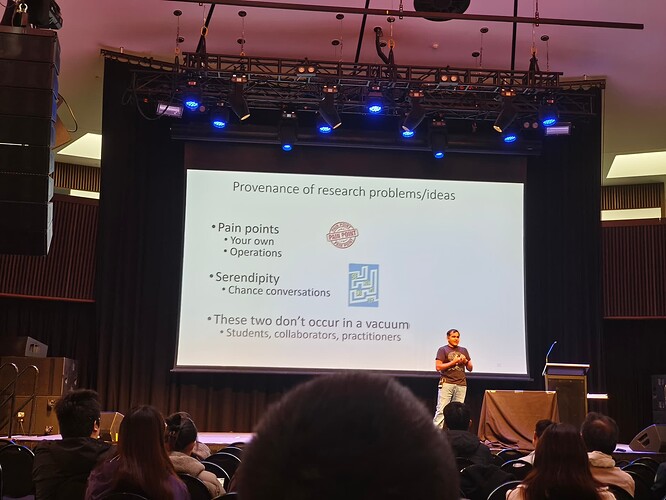

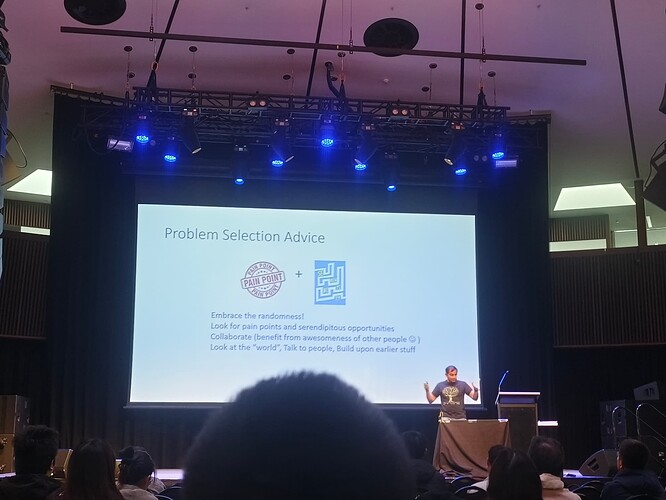

Problem Selection:

The speaker highlights two primary sources of research ideas:

- Pain points: Identifying challenges faced by oneself or others in the field.

- Serendipitous conversations: Chance encounters leading to new insights, datasets, or collaborations.

The speaker encourages embracing a non-linear, iterative process of problem selection, involving continuous exploration, collaboration, and learning from others.

Key Takeaways:

- Articulating research goals clearly is crucial.

- Problem selection is often a non-linear, iterative process.

- Pain points and serendipitous conversations can spark research ideas.

- Collaboration and learning from others are essential.

The talk encourages researchers to embrace a structured yet flexible approach to research, emphasizing the importance of clear communication, continuous learning, and collaboration.

Q&A for Part 1

Q1: As a graduate student or early-career researcher, how can I address questions about time, cost, and skills?

A1: As a graduate student, you don’t need to worry about costs—that’s your advisor’s responsibility. Focus on whether you have a feasible solution. If resource constraints are an issue, consider rethinking the problem to find a cheaper, faster solution. It’s important to consider the time and mid-term goals, and break the problem down into smaller, more manageable sub-problems.

Q2: Should we have separate sets of questions for grants and papers?

A2: The first four questions are applicable to both grants and research, while the last four are more specific to grants. Grants typically require a more grandiose and ambitious vision, whereas papers are more narrowly focused on a single sub-problem. Grants can involve a collection of problems that work toward a larger goal.

Q3: How can I effectively combine multiple small ideas when writing a grant proposal? Any advice?

A3: When writing a grant proposal, it’s often easier to start with a top-down approach, focusing on the overarching problem even if you’re unsure of the solutions. Grants are more about addressing the problem itself, whereas papers are solution-oriented. Develop a plan with the understanding that it may change as the research progresses. Grants are a commitment to pursue something, but they are not strict contracts, so there’s flexibility to adjust your approach as needed.